Kinder Morgan downplayed the impact of a decision by Hays County Commissioners to rescind permission to cross county roads. That decision was made in the wake of a construction accident March 28 that sent tens

of thousands of gallons of drilling mud and drilling fluid into the Trinity Aquifer.

More than a month later, work remains stalled at that site in Blanco County near Chimney Rock Road.

Kinder Morgan spokesman Allen Fore told the Hays Free Press that the commissioners’ decision will have...

Kinder Morgan downplayed the impact of a decision by Hays County Commissioners to rescind permission to cross county roads. That decision was made in the wake of a construction accident March 28 that sent tens

of thousands of gallons of drilling mud and drilling fluid into the Trinity Aquifer.

More than a month later, work remains stalled at that site in Blanco County near Chimney Rock Road.

Kinder Morgan spokesman Allen Fore told the Hays Free Press that the commissioners’ decision will have little impact because the project only crosses five Hays County roads and two crossings in eastern areas of the county have already been completed.

He described the original agreement with the county to allow road crossings as “very technical,” and part of an “original round of permits” secured “some time ago.”

He also explained the difference between a “bore” under a roadway and horizontal drilling, which is what went awry under the Blanco River.

Horizontal drilling, he said, is done on a “gradual slope” to a depth of 30, 40 or 50 feet, while road crossings are a simple bore accomplished from “bore pits” on either side of the road. Those are typically 8 to 10 feet below the road, something Fore said was according to county specifications.

The county’s action does not affect state highways, Interstate 35 or the toll road Texas 130. Work has not yet started on CR 218 at Pump Station Road, CR 220 at Mt. Sharp Road and CR 244 at Ledgerock Road, all in west Hays County. Crossings have already been accomplished at CR 140 and CR 158 in Hays County est of IH-35.

Fore said he spoke April 24 with county officials including Pct. 3 Commissioner Lon Shell, who brought forth the motion to rescind the permissions, and with Pct. 4 Commissioner Walt Smith, and the transportation department.

“We will be talking further as they make what was passed into an actual process,” Fore said.

The motion, as passed, calls for Kinder Morgan to stop “road cuts across and/or drilling under roadways” until such time as the company “has complied with the Railroad Commission Notice of Violation and provided the plan for ‘moving forward … in a manner which will prevent further impact to groundwater and surface water,’” and also that the company provide the county “with a detailed geology report for each proposed county road crossing specifically identifying whether the area is underlain by karst.”

Shell also said he would “like to instruct staff to develop a policy for approval by court that, in the event that karst features or geology are present, Kinder Morgan should be made to perform ground penetrating radar (GPR) studies to identify voids, caves, crevices or other features that could post the risk of loss of drilling fluid and identify neighboring groundwater wells, which shall be reviewed by Hays County prior to any permit activation.” Shell did not respond to an email seeking further comment.

Fore said details of the county’s requirements are “still being pushed out.”

“The resolution is a little vague,” he said. “It’s certainly something we can work with the county on — a process we can cooperatively work through.”

The event that brought about the county resolution was an accident that occurred when a contractor engaged in horizontal drilling under the Blanco River hit one of the area’s numerous karst features (which include caves, sinkholes and springs). The rupture fouled some water wells in the immediate area and the energy company has said it is working with its own karst expert as well as regulatory agencies to mitigate the damage.

The route of the 430- mile natural gas pipeline shows a second Blanco River crossing in Hays County. Work has not yet begun there, but is proceeding elsewhere across Blanco, Hays, Caldwell and other counties on the way to near Houston, where the product will be bound for foreign markets. Authorities have noted that the pipeline construction has not yet entered areas with the most known karst features.

It’s not clear what the effect of the disruption of the oil market that occurred in mid-April has had on the project, if in fact there is any impact. Even before the COVID-19 crisis, marketwatch.com reported on Feb. 13 that “natural gas figures settled at $1.766 per million BTUs, the lowest finish since March 2016, according to Dow Jones Market Data.” The site went on to say the reason for the drop in natural gas prices was due to “warmer than average temperatures, reduced consumption and increased supplies.”

On April 22, Reuters published a story saying Kinder Morgan “reported a smaller-than-expected quarterly profit and cut its adjusted core earnings forecast for the year, following a coronavirus-induced decline in fuel demand and a crash in crude prices.”

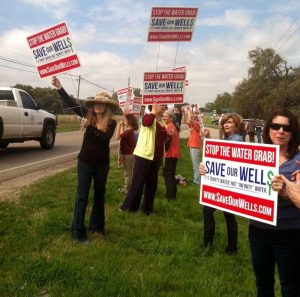

When details of the pipeline became public, a coalition formed in late 2018. Organizations including the Wimberley Valley Watershed Association (WVWA) and the Trinity Edwards Spring Protection Association

(TESPA) voiced opposition and threatened legal action over the pipeline’s route. They have pointed specifically to the presence of karst features and the likelihood of aquifer contamination through construction accidents.

Because the pipeline is considered infrastructure, Kinder Morgan was able to use the power of eminent domain to secure easements over the objections of landowners, and Blanco County landowners successfully took the energy company to court in 2019.

Under Texas law, the project only needed approval from the Railroad Commission, which does not include environmental issues in its permitting process. The WVWA and TESPA are already involved in legal action that charges the PHP violates the Endangered Species Act. Much of the route is through the habitat of the endangered golden-cheeked warbler, which is currently in its breeding season.