HAYS COUNTY — “Tell me something sexy for encouragement,” Thomas Geredine Sr., 73, said to the 14-year-old.

When Sophia Olivarez, an incoming freshman at Johnson High School, heard those words, she was stunned. She didn’t know what to say. “I don’t know what you mean,” Olivarez said. After practice, she climbed into her mother’s car and sobbed.

The date was May 30, 2019. Little did Olivarez know that her life would soon change, sending a ripple effect through her family and forever shaping her view of the justice system. But these experiences would only strengthen her resolve, as she encourages other victims of sexual abuse to come forward and share their own stories.

———

Olivarez, now 18, had been taking private track lessons from Geredine, a former NFL player, for the past two or three months. She said that her first impressions of the private track coach were positive. But slowly, inappropriate comments and touching crept into their interactions.

“I thought he was a nice guy, like he just seemed like a track coach that wanted to help,” Olivarez said. “I didn’t see any problem with [him] at first. And then there were little things along the way. Any chance he could get, he would just touch us. If it was inappropriate or not, he would just always keep a hand on us.”

Two weeks prior to that practice — the final straw that changed the trajectory of her and her family’s lives — the track coach was stretching her prior to a race. Very quickly, his actions escalated, she said.

“There was a track meet that we did outside of school where me and him were … behind [my parents] and he was going to stretch my leg, so it wasn’t tight before the race,” Olivarez said. “He would just get too close. He’d be stretching my legs, but then he would get way too close to [my vagina], just like brushing his fingers there. I didn’t really say anything because I didn’t totally know what was happening in the moment. Until I did.”

After confessing everything that had happened with Geredine, Olivarez’s mother, Annie Kuhn, was in disbelief. He had come highly recommended as a private track coach. Geredine was beloved by the community.

“He was always known to the community,” Kuhn said. “It sounds so stupid as a parent now, but it was kind of like one of those hindsight is always 20/20 things. He was just known to everybody. So, we kind of put this like blind trust in him. He was absolutely recommended by so many people and you look back and you’re like, ‘Oh my god.’ It’s like a bad movie. He was a quintessential narcissist; he got one over on us for sure.”

Even before her daughter’s confession, Kuhn began to notice how the coach would try to separate the athletes from their parents.

“He would try to take them behind the bleachers, like try to make distance between the parents,” she said. “It was like he was trying to do everything possible to get the parents out of sight of the kids.”

But after Geredine’s inappropriate comments, Kuhn transitioned from consoling her daughter to embracing a mother’s fury.

“You know, I’ve been molested as a child. So, you instantly go into wanting to protect your children,” Kuhn said. “In my head, I’m driving home and thinking, ‘What do I need to do?’”

She decided to call him and confront him herself.

“Initially, I was thinking in my head that I need to get this guy to admit what he did,” Kuhn said. She decided to record the interaction for the impending investigation.

“Did you say something to Sophia tonight that would have upset her?” Kuhn asked, her voice trembling with rage, according to a recording obtained by the Hays Free Press. “The word sexy should not exit your mouth when talking to my daughter.”

During the call, Geredine was demure, but never denied what he said, insisting that there must have been a misunderstanding.

“I must have said something other than that,” he said. “I’m not disclaiming [what she said]. I’m just saying that whatever it is has to be out of context.”

He then apologized — a move that shocked Kuhn later upon reflection.

“Regardless, I am apologizing. It wasn’t meant to be however it was interpreted. I may have made a comment,” Geredine said. “I’m not pointing a finger at her at all. She’s not to blame for anything. I’m certain I said something inappropriate, but the content is what I’m trying to verify. I speak out of turn, I say things and all I can say to you and to her is that I am truly, truly sorry, but that don’t take away the pain or hurt or inappropriateness.”

Neither of them realized how prophetic those words would come to be.

———

Kuhn decided to call the Hays County Sheriff’s Office, which sent a detective to interview Olivarez and take her statement (HCSO Detective Jennifer Baker could not be reached for comment).

Ultimately, Geredine was charged with two counts of indecency with a child by sexual contact, a second-degree felony. The court record suggests multiple victims in this case. (The other victim will not be named in this story.)

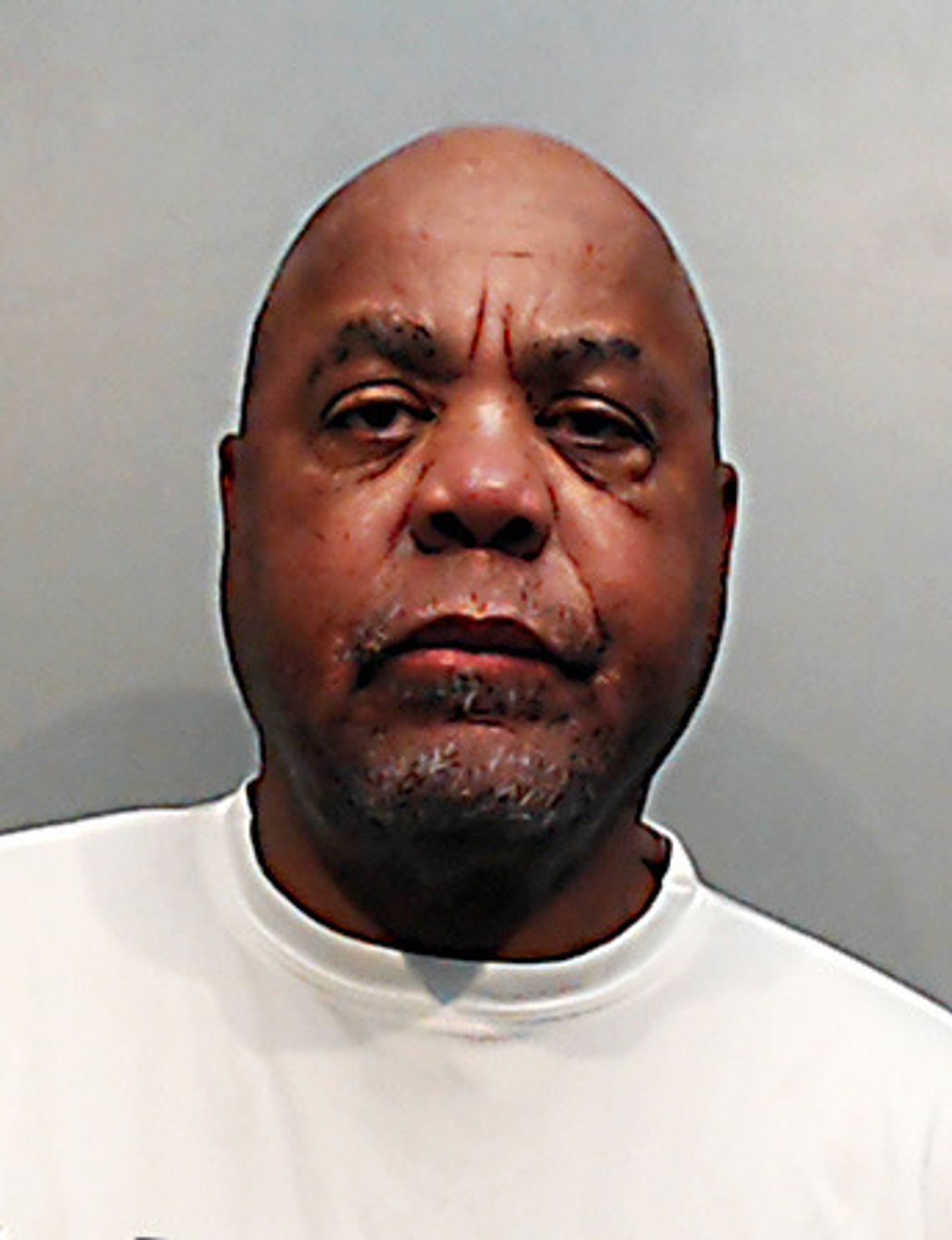

Geredine, of Kyle, was arrested by the Kyle Police Department on Aug. 5, 2019 and released on an $80,000 bond.

After he was indicted on Jan. 1, 2020 and arrested by the Hays County Sheriff's Office on Jan. 22, 2020, Geredine was released on an $80,000 bond the same day — just a few months before COVID-19 shut down the U.S. As the pandemic ravaged the world, the case dragged on and on.

They say that justice delayed is justice denied. A jury trial was initially set for Sept. 21, 2020, then reset for Jan. 5, 2021. It was then reset for April 5, 2021, then for Sept. 13, 2021, then Dec. 6, 2021, Feb. 28, 2022, April 24, 2022, June 6, 2022, July 18, 2022, Aug. 29, 2022, Oct. 11, 2022 and Jan. 17, 2023.

“We were going to go to trial and she was ready,” Kuhn said. But Olivarez would never take the stand. Nor would Geredine’s other victims.

Three months before his last scheduled trial, Geredine’s former defense attorney in an unrelated case, Kelly Higgins, had won the election for Hays County District Attorney, creating a conflict of interest (Higgins was not his attorney at the time of the election nor did he have any involvement in the resolution of this case).

When Higgins took office, there was, indeed, a conflict of interest.

“With respect to conflicts and recusals generally, if I was actively representing someone when I was elected, I have recused myself and a prosecutor pro tem from another county has been appointed to handle the case. Because I would potentially have knowledge of confidential attorney-client communications related to the pending charges, my office cannot handle the case. For defendants that I represented at some point in the past, most are still resulting in a recusal and the appointment of a prosecutor pro tem, although some defendants are choosing to waive any conflict. I, myself, am walled off from any direct involvement in those cases,” Higgins said.

“This means I do not contribute in any way, that I am kept uninformed as to the progress of the case and that I do not receive reports when cases are resolved. This practice protects both the defendant and the state from any conflict. Under this approach, I am not able to influence the case either by exploiting confidential information or by securing special treatment for a former client. In short, the practice of walling off an attorney after waiver of conflict keeps both parties safe under the law," he continued.

“The new prosecutor spoke with the defense attorney, who indicated that they were willing to plead guilty as long as the defendant would not have to register as a sex offender. The new prosecutor contacted the family of the victim and explained the situation,” Higgins said. “She informed them that because I had represented the defendant in the past, our office would have to be recused if there was a trial and a prosecutor pro tem from another county would take over. The case could be settled by plea bargain without a recusal because the defendant was willing to waive any conflict. The offer was not contingent on waiving the conflict.”

This conflict of interest was a fact that led to the family agreeing to essentially settle for less than what they believed was true justice.

“She was ready [to go to trial]. I didn’t want to push it on her, but she was like, ‘No, I want to do this.’ And then it was like, ‘Oh, well, maybe we don’t want to do this because there’s a chance that he would not be prosecuted at all,'” Kuhn said. “So, that’s why we kind of felt like, ‘Okay, let’s just take the deal because at least he’ll get something.’ They called and we discussed it as a family and we just felt a little bit like it’s been dragging on for so long. We just felt like we didn’t really have a whole lot of options. Our biggest thing was we wanted to make sure he never worked with children again.”

On Jan. 24, 2023, Geredine accepted a plea agreement for one count of injury to a child, a third-degree felony.

According to Hays County District Attorney’s Office Victim Assistance Coordinator Erin Dupalo, the terms of the plea include the following: 10 years supervised deferred adjudication on a third-degree felony injury to a child - bodily injury charge, a $1,500 fine, a $60 per month supervision fee, a psychological/drug/alcohol abuse evaluation with counseling/treatment as recommended, 350 hours of community service, no contact with the victims and sex offender treatment. He is prohibited from working in schools with minor children 10 years of age and younger.

He did not, however, have to register as a sex offender — a fact that enraged Geredine’s own daughter, Sarah (whose name has been changed for privacy), who has her own story to tell, revealing a pattern of abuse at the hands of her father.

———

While the world around her praised the sports prodigy, Geredine’s daughter grew up with a less-than-ideal view of her father. The tween would allegedly see her father kicked out of the NFL due to theft and cheat on her mother; she witnessed the beating of a mistress and endured sexual assault at his hands, according to Sarah.

“All that my mom went through, it didn’t indicate that he would do what he did to me,” she said.

Suspicious moments happened far before the triggering incident that permanently removed Geredine from her life.

“There were things that happened that I didn’t really realize what was going on because of my age … There was this game he would play where he would sit me on his lap and tell me I was riding a horse. Well, when I was a kid, I thought I was having a fun lap ride, but looking back, that was creepy. That was probably something perverted and I just didn’t know because of my age,” said Sarah.

After Geredine and her mother divorced, she often traveled to Texas to visit her father along with her new baby brother. The summer of her sixth grade year scarred the already trauma-riddled girl.

Sarah was nearing 12 years old and had brought a photo of a school crush to Austin that summer. Interested, her father inquired about her feelings toward boys. What allegedly happened next gave her an answer that stuck with her for the rest of her life.

“He molested me. He molested me over a whole weekend,” she said. “He did everything but penetrate me — with his fingers, with his mouth, with everything that you can imagine that someone would do. He told me how good of a kisser I was.”

Paralyzed with fear, Sarah had no way to protect herself and was forced to endure the alleged assault.

“He was touching me, kissing me, fondling me, touching my private parts, asking me to kiss his penis. All these things that I knew were wrong, but I was petrified and there was nothing that I could do really,” she said.

Sarah was separated from her father and subsequently forced to lose contact with his side of the family, including close relatives such as her brother and grandma.

Just as many victims of abuse do, his daughter struggled with accepting the trauma she allegedly experienced. She often called Geredine and spewed anger toward him.

In a moment of curiosity, a feeling that occurred periodically throughout her life, she Googled her father’s name.

“One day, something made me Google his name. I don’t know what made me do it, but I did and one click led to another and that’s where I saw these new accusations … I became very involved in wanting to see him punished because it's like, ‘How dare you, [all these years] later, to have gotten away with this and you’re still doing this?’” she said.

Because Geredine was never punished for the alleged abuse, she felt obligated to reach out to the prosecutor to offer help and another perspective on the ongoing case.

“I wrote to the prosecutor and I told him that this happened [to me]. ‘If you need a witness. If you need a statement, whatever. I want to help because I know the damage that it can do to a young girl. Anything I can do to help.’ I wanted him to go to prison,” Geredine’s daughter said. “It would have felt like redemption for me, too.”

For months and months, Sarah packed her bags, found a babysitter for her daughter and planned her statements, only to be told each time that she would not be flying out to Texas to testify due to the trial being reset again and again.

“They kept extending the trial and it almost felt purposeful. I’ve heard that if you keep getting extensions, sometimes things fall off … The icing on the cake was [that the prosecution wasn’t] going to make him register as a sex offender,” she explained.

Though the alleged experience only lasted 48 hours, the trauma has long-lasting effects. Throughout her adult life, she has seen the impact on her adolescence, her love life, her personality and her experience as a mother.

“It’s shaped me into a woman that doesn’t know how to trust a man or relate to a man …. I always look at them in a way that I don’t trust them,” she said. “It’s made me very overprotective as a mother. My daughter tells me I put the mother in smother … It’s made me an overprotective, untrusting woman that can’t relate to men.”

Similarly, Olivarez, who still is an active athlete, finds it hard to trust her coaches, who are predominantly men, and hasn’t let her guard down in the four years following the incident.

Kuhn has taken on a different type of trauma: “As a parent, you instantly take on that guilt … You take on that, ‘I should have protected my child, I should have seen that sign, I should have known what he was doing.’ Because you look back and you think of all the little signs [you should have seen],” she said.

The outcome of the case was not what either victim had in mind. For every individual involved, prison — or at least a sex offender registration — would have been justice.

“I don’t like that he wouldn’t have any title saying that he did any of that. It makes me angry. I wish he did,” said Olivarez.

Sarah echoed that anger.

“I do think the justice system failed these little girls for the simple fact that he doesn’t have to register as a child sex offender,” she said. “In my eyes, he’s kicking and will do it again …. He doesn’t deserve to live this whole lie without being exposed … I’ve felt like justice was never served on my behalf and then that made me feel like justice wasn’t being served on their behalf. It feels like he’s gone through his whole life with no repercussions and almost being admired because he was a professional football player when really, he’s a thief, a fraud and a child molester.”

For Kuhn, she sees this as the justice system not taking the safety of children seriously: “To me, it's very disheartening because you think our children are our number one priority and we should be putting their safety first and knowing that it was kind of like, ‘Oh, well, here — at least we’ll give you this.’ It felt like our children are second rate. That their safety doesn’t really come first,” she said.

Despite all that they have endured, the victims are resolved not to be brought down by the alleged actions of Geredine.

Olivarez graduated from Johnson High School in May and will be continuing both her education and track career at Belmont Abbey College in North Carolina.

Sarah recently graduated with her master’s degree and her daughter is following in her footsteps in pursuit of her own master’s degree.

“[The assault] didn’t stop my education and it didn’t stop my ambition to try to do good things,” she said.

Geredine’s daughter is proud of those victims who came forward, finally breaking the cycle of abuse.

“Those girls were brave enough to tell on him,” Sarah said.

Olivarez also encourages other victims of sexual abuse to come forward with their claims and tell their stories.

“[I’d want to tell victims] that speaking up is not as scary as you think it is. [I would] just tell them to speak up,” Olivarez said. “Just don’t feel like it’s your fault because it’s not. It can be hard, especially if you’re being threatened by the person.

“But it’s worth it.”

Thomas Geredine Sr. declined to comment on this story.

Alleged child molester pleas guilty to injury to a child

HAYS COUNTY — “Tell me something sexy for encouragement,” Thomas Geredine Sr., 73, said to the 14-year-old.

- 06/28/2023 07:15 PM