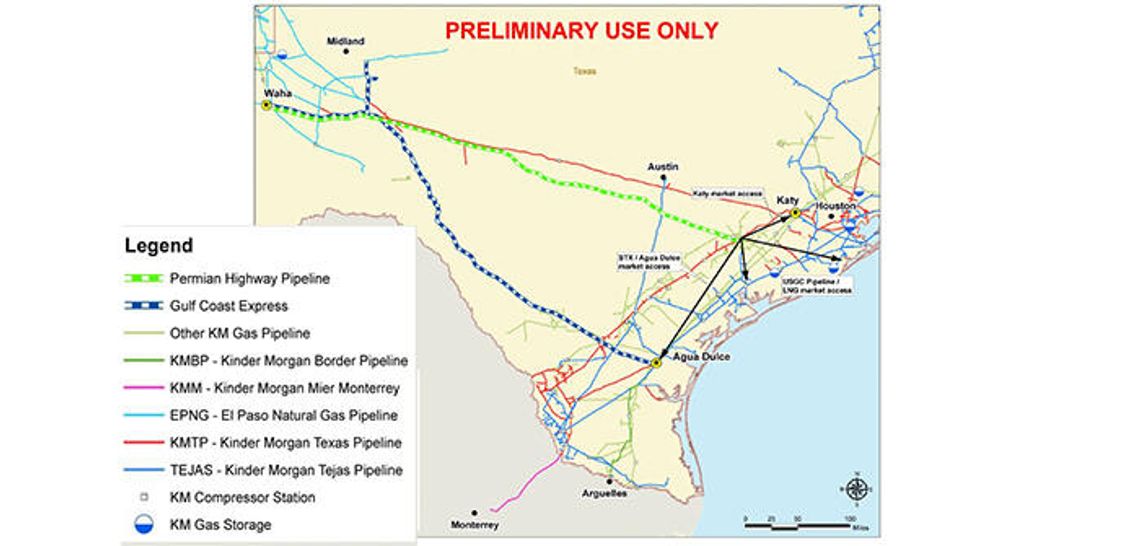

Protecting landowners from a proposed 430-mile natural gas pipeline is the focus for Hays County officials as they seek to talk with Kinder Morgan about alternative routes for its proposed Permian Highway Pipeline.

But the fight now involvesTexas law, which could grant Kinder Morgan eminent domain status.

PLEASE LOG IN FOR PREMIUM CONTENT. Our website requires visitors to log in to view the best local news.

Not yet a subscriber? Subscribe today!